Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Download printable versionOverview

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the one of the most common digestive conditions. It’s defined by belly pain along with a change in bowel habits. Rates of people living with IBS vary between countries. IBS affects 4 in 100, to one in 10 of the global population. Twice as many women are diagnosed with IBS than men. A study of pelvic pain in transgender men and gender-diverse adults assigned female at birth found just over a third had IBS. Doctors can diagnose IBS at any stage of life. But the most common age of diagnosis is between 20 and 40 years old.

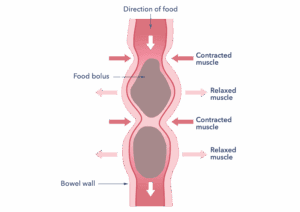

How food (food bolus) moves along the gut

This diagram shows how poo is moved through the bowel by contractions of the muscles in the bowel wall. These normal gut contractions can cause pain in the bowel for people with IBS.

Causes

Doctors know IBS as a disorder involving the communication between the gut and the brain. Doctors call this a disorder of the gut brain interaction (DGBI). Nerves supply the gut and enable it to work correctly. In IBS there is a fault with this interaction, and this causes the symptoms. The nerves can be too sensitive to the way the bowel normally moves. This sensitivity causes pain. Doctors call this pain visceral hypersensitivity.

For some people a gut infection or antibiotic use can cause the condition to start. There is a tendency for IBS to run in families, but no gene for IBS has been found. But it’s hard to separate genetics and the family environment. Changes in the microbes normally found in the gut have been linked to IBS.

These changes may be due to the microbe’s environment, for example diet and medicine side effects. A condition called endometriosis is linked to IBS. The nervous system, emotional state, the immune system, and gut microbes seem to interact. There may be groups of people with different causes of their IBS. More research is needed to find out the causes.

Diagnosis

If you have symptoms, make an appointment with your doctor. The GP will review your symptoms. They will also do any tests needed to rule out other diseases. Don’t be tempted to self-diagnose. Doctors use guidelines to help them to diagnose IBS. The pain happens for an average of one day per week or more for at least three months and is associated with a change in bowel habit. At times, bowel symptoms can be caused by drugs you might take for other conditions. It’s worth discussing this with your doctor to see if a medicine switch can be made. Do not stop taking your medicine without talking to your doctor first.

There is no test used in the NHS for IBS diagnosis. The following blood tests might be used to rule out other problems:

- A check for anaemia. This is a low haemoglobin level in the blood, which can be caused by low iron levels. Anaemia is not a symptom of IBS. It could show other diseases.

- A check for how well the liver and kidneys are working.

- A check to see if there is inflammation in the gut. Doctors use a stool test called faecal calprotectin. If results are normal this can help show that the symptoms are not caused by Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. These are forms of inflammatory bowel disease.

- A check for coeliac disease. Do not alter your diet before testing, you need to be eating gluten to make sure the test can identify it.

The GP will want to rule out other diseases but will probably be able to make a diagnosis based on the described symptoms. After ruling out other conditions with a few simple tests, doctors can be confident the diagnosis is IBS. This then allows the person to try treatments to reduce the burden of symptoms.

IBS is one of the most common reasons for a visit to the GP.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of IBS include:

- Belly (abdominal) cramps. They can be uncomfortable or painful.

- Abnormal bowel habits. You could have diarrhoea, constipation, or both.

- Wind, bloating and distension (a widening of the girth of the belly).

- Mucus present in poo.

Other symptoms can include feeling tired and sick, backache, and bladder issues.

About 1 in 3 people have IBS-C, causing constipation symptoms. Another third of people have IBS-D, with diarrhoea symptoms. Others don’t fall into a specific pattern (IBS-M). IBS-M abbreviation is used for people with both constipation and diarrhoea symptoms. Symptoms can occur daily, or they can come and go over weeks or months. They can alter over time and may not always be present. Bowel movements and stool frequency may vary. Symptoms often ease after a bowel movement. The unpredictability of symptoms can be challenging.

Symptoms that may need further investigation

These symptoms are not typical of IBS. They may signal other diseases. If you have concerning symptoms, see your doctor as soon as possible. Do this even if you already have been diagnosed with IBS. Symptoms include a persistent change of bowel habit for 4 weeks or longer, especially if you:

- Are over the age of 40.

- Are passing blood from the back passage.

- Have unintentional weight loss of more than 2kg.

- Have diarrhoea waking you from sleep.

- Have a fever.

- Are diagnosed with anaemia (low haemoglobin levels in the blood diagnosed by your GP using a blood test).

Tell your doctor if you have a family history of bowel disease such as cancer, colitis or Crohn’s disease.

Treatment

Once diagnosed, most people can find effective ways to live with IBS. Treatment may need to be altered according to the symptoms.

Regular exercise should be part of a healthy lifestyle. Aim to include some activity in your daily routine. If you can make some leisure time available use it for activities that help you relax.

Healthy eating habits

Some people find that following healthy eating habits helps.

IBS dietary management

Over 8 in 10 people with IBS report food related symptoms. The recommendations may vary depending on whether you have constipation, diarrhoea, or both. If a diet is suspected of causing symptoms, your GP can advise on simple diet changes. These changes are based on the British Dietetic Association and the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. This includes eating three healthy meals every day. It also means limiting alcohol and caffeine intake. Eating small portions slowly can help with bloating. Changing your fibre intake is good to try depending on the type of IBS you have. Some people with diarrhoea find reducing dietary fibre improves symptoms. Others with constipation may find a soluble fibre supplement helpful. Also, avoid eating fatty and spicy foods. If initial dietary changes do not help, the GP may refer you to a dietitian. If you would like an more detailed information sheet on diet and IBS, visit the British Dietetic Association website.

Identifying trigger foods

If the simple advice doesn’t help, quality standards of care say a trained practitioner should be involved. Only state registered dietitians are trained to advise on exclusion diets. The dietitian will try to find any foods that cause IBS symptoms. They may remove certain foods from your diet. Then, they add them back slowly. This can identify which items trigger symptoms.

A particular form of this diet is the low FODMAP diet. This diet excludes short-chain fermentable carbohydrates. These carbohydrates can be a cause of symptoms for some people. It works for about a half to two thirds of people with IBS. There is little evidence that a gluten-free diet may help with IBS symptoms. More research is needed in this area. Do not try exclusion diets on your own, only do so if a dietitian recommends them. Unsupported use of low FODMAP internet sites and printed low FODMAP diet sheets should be avoided. If you have, or had, an eating disorder, exclusion diets may not be the best treatment for you. There are other treatment options to try instead.

Probiotics

People with IBS can have different gut microbes than people without IBS. A few studies have suggested probiotics can help some people. Trying probiotic supplementation for up to 12 weeks is recommended2. If you find no improvement in symptoms, stop using it. If you do have improvement, you should continue to take it. This is because there is little evidence that probiotics repopulate the bowels’ own microbes. There is a cost associated with this treatment.

Medicines

Simple lifestyle changes should be the first approach for example diet and exercise. If this approach is not effective, then medicines can be tried to improve symptoms. IBS is an individual condition so if one medicine is not helpful another could be tried.

IBS with constipation can be treated with laxatives. You can get them prescribed or buy them over the counter. The dose might need to be adjusted depending on their effect. Guidelines recommend avoiding lactulose as this might make symptoms of wind worse. Talk to a pharmacist about this if you are struggling to achieve the right dose for you. If laxatives available from your GP don’t work, gastroenterologists can prescribe other options such as linaclotide. If simple IBS treatments have not been effective, then ask your GP for a referral.

For IBS with diarrhoea, loperamide can be used. This medicine increases gut transit times, slowing the passage of poo through the gut. It promotes water reabsorption in the body. Second line medicines are also available for people with IBS with diarrhoea if treatments available from your GP do not work. For example, ondansetron. Ask your GP for a referral to a gastroenterologist if symptoms continue.

Another option for people with diarrhoea are intestinal adsorbents. These are available over the counter as ‘gels’ for treatment of diarrhoea.

For abdominal pain and wind, medications to reduce bowel spasm can be used. These include mebeverine, alverine, and hyoscine butyl bromide. Peppermint oil capsules may ease spasm type pain, but they can also worsen reflux in people who have both.

Medicine called gut-brain neuromodulators act on the gut and brain. They reduce IBS symptoms in low doses. If simple measures have not helped, your GP might consider using a drug called amitriptyline4. This can also help reduce sleep problems in people with IBS. You may have heard this medicine is used to help people who have depression, particularly at higher doses. This is not how it works in people with IBS and the doses used in IBS are generally much lower than those used for depression. In people with IBS this medicine improves signalling between the brain and the gut to help reduce IBS symptoms.

Ask your GP for a referral to a gastroenterologist if symptoms continue. New drugs are also being developed.

Gut- specific behavioural treatments

If symptoms continue after 12 months of treatment, then a more holistic, rehabilitative approach with gut-specific behavioural therapies (otherwise known as brain-gut behavioural therapies) can be considered. These treatments are amongst the only treatments that have been shown to work when a person’s symptoms have not responded to medical treatments. Unfortunately, these services can be difficult to access with long waiting times. Your GP can advise.

Gut-directed hypnotherapy has evidence that it can be helpful to treat IBS. The aim is to induce a deep relaxation to teach the person skills for self- management of IBS. You can get gut-directed hypnotherapy treatment from approved therapists. Therapists should be members of the British Association of Clinical and Academic Hypnotherapists or the National Council for Hypnotherapy. There may be a cost associated with this treatment.

Experts have also suggested using IBS specific cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to treat IBS. It is a psychological based therapy based around a five-systems model. It proposes that thoughts, actions, and emotions all interact. This includes thoughts, behaviours, and bodily functions. CBT can reduce IBS symptoms. It does this by teaching the individual to relax the body and reduce symptoms. Your doctor can prescribe CBT.

Online platforms, and group interventions have been shown to be effective for both gut-specific CBT and gut-directed hypnotherapy. There are now also several emerging mobile applications (apps) which deliver self-directed CBT and self-directed gut-directed hypnotherapy skills training for IBS. There may be a cost associated with this treatment. Mobile brain-gut behavioural treatments such as these apps may be effective for some people with IBS. If you are considering an app, please ask the organisation for their research evidence that it has been shown effective for people with IBS.

Those with more complicated IBS with severe symptoms may require a more individualised and personalised approach to treatment delivered by a therapist.

Building a good doctor-patient relationship is key to managing IBS. Your doctor can help you with how to manage the condition and reduce symptoms. This partnership can help improve your quality of life. IBS is very individual, and you’re the best person to know what may work for you. Try different treatments. They may not all work, but there are several to try. Sometimes, it might take a combination of them to work. According to NICE’s quality standards, you can request a review. This enables newer treatments to be considered. A review is not provided automatically. You should ask your doctor (usually your GP).

Support

What to ask your doctor?

These are some useful questions you can ask your doctor:

- Have I been fully checked for other bowel conditions?

- Are there any medications that would be useful for me to take?

- May I be referred to a dietitian?

- Can I have a regular review for my IBS?

Further information and support

Guts UK

Call our freephone Helpline on 0300 102 4887 (Monday to Friday 10am to 2pm, excluding Bank holidays) or use our Helpline webform to submit your query online and a member of the team will be in touch. Alternatively, you can email us at helpline@gutscharity.org.uk.

If you would like a printed copy of this leaflet, please email us at info@gutscharity.org.uk, or call us on 020 7486 0341.

For one of our free Can’t Wait cards, which can help you access public toilet facilities urgently, please complete our online order form.

RADAR key

You could also purchase a RADAR key to access some locked toilets. These can be purchased for a small fee from several organisations across the UK.

NICE guidelines for IBS

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provide guidelines that doctors can follow when diagnosing and treating people with IBS. NICE also produce Quality Standards for IBS and these standards show what good service provision should look like. There are four standards currently:

1. Considering that people should have had a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease ruled out before providing a diagnosis of IBS.

2. Giving a positive diagnosis depending on symptoms meeting the diagnosis criteria for IBS and not just based on a process of excluding other diagnosis. Testing that may be required is listed.

3. Adults getting a referral to a trained practitioner if symptoms continue after first line dietary advice (see the IBS guideline) has not been effective to manage symptoms and a restricted or exclusion diet is required. Please note the ONLY trained practitioners are dietitians registered with the HCPC. This standard can facilitate a referral to a dietitian for a low FODMAP diet.

4. Many people live with IBS longer term without knowing about new treatments. This standard is an opportunity for a person with IBS to discuss their symptoms and how these are managed with their healthcare professional. An appointment to review your IBS can be requested at a frequency agreed by the person and their healthcare professional, and can take the form that they feel is the most appropriate (such as attending the GP practice or a telephone conversation). Please note you have to request this from your doctor (usually your GP) it is not automatically provided. Read about the standards here.

Research

Discover more:

Copyright © 2026 Guts UK. This leaflet was published by Guts UK charity in May 2025 and will be reviewed in May 2027. The leaflet was written by Guts UK and reviewed by experts in IBS and has been subject to both lay and professional review. All content in this leaflet is for information only. The information in this leaflet is not a substitute for professional medical care by a qualified doctor or other healthcare professional. We currently use AI translation tools on our website, which may not always provide perfect translations. Please check for further explanation with your doctor if the information is unclear. ALWAYS check with your doctor if you have any concerns about your health, medical condition or treatment. The publishers are not responsible or liable, directly or indirectly, for any form of damages whatsoever resulting from the use (or misuse) of information contained or implied in this leaflet. Please contact Guts UK if you believe any information in this leaflet is in error.