Oesophageal Cancer

Download printable versionOverview

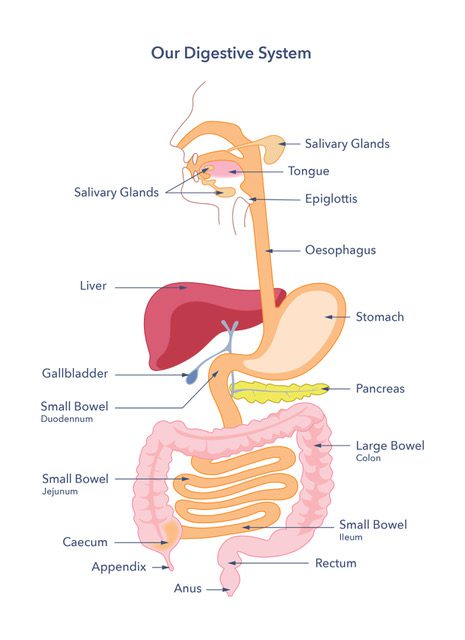

What is the oesophagus?

The oesophagus (often known as the gullet or food pipe) is a muscular tube that leads to the stomach. Food and drink pass from the back of the throat into the stomach through the oesophagus. When food is swallowed, the muscles in the oesophagus shorten (contract). The muscles push food and fluid down into the stomach. At the lower end of the oesophagus is a muscular valve, called the oesophageal sphincter. It sits where the oesophagus joins the stomach. The oesophageal sphincter prevents food and fluid from being pushed upwards from the stomach.

Cancer of the oesophagus

Oesophageal cancer develops when the cells that line the oesophagus are damaged. The damage causes the oesophagus to narrow and makes swallowing hard. At first, solid food tends to stick in the oesophagus. This is followed by difficulty swallowing liquids as the cancer grows.

Cancer cells may spread beyond the oesophagus to nearby structures, like lymph nodes and blood vessels in the chest and abdomen. Cancer cells may also be carried in the blood to form secondary tumours (called metastases) in the liver or elsewhere.

Most cancers in the upper two-thirds of the oesophagus are known as squamous carcinomas. This is because they develop from the squamous (skin-like) cells that line the oesophagus.

Cancers in the lower third of the oesophagus, where the oesophagus joins the stomach, are usually adenocarcinomas. They develop when the normal flat skin-like lining of the oesophagus is replaced by stomach-like cells.

Oesophageal cancer is the 14th most common cancer in the UK. About 9,400 people are diagnosed each year. 7 of 10 adenocarcinomas diagnosed in the UK are in males. There is no sex difference in squamous cell carcinoma rates. Most people diagnosed are over 70 years old, but diagnosis is increasing in younger people.

Causes

Risks and causes of oesophageal cancer

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Important risk factors for developing SCC include tobacco use or drinking excessive amounts of alcohol.

- Smoking causes 7 in 20 oesophageal cancers. Chewing tobacco also increases the risk of SCC.

- Alcohol consumption significantly increases the risk of SCC.

- New evidence shows that drinking very hot beverages (more than 65°C) can also increase the risk of SCC.

- The human papilloma virus can increase the risk of SCC at times.

- Rare genetic causes, like having ALDH2 deficiency, at the same time as drinking too much alcohol, also increases the risk.

- The risk is also slightly higher with a skin condition called Tylosis.

- There is a disorder of the muscles of the oesophagus, called achalasia. Achalasia causes a failure to relax the muscular valve at the bottom of the gullet. Achalasia can very occasionally lead to cancer.

- Some communities use areca (betel) nut in paan. Researchers have linked use of areca nut to a higher risk of SCC. Tobacco is also used with paan.

- SCC is common in parts of Africa and China. The local diet and food preservation methods, or other lifestyle factors, might be a risk factor.

- Oesophageal Lichen Planus can also rarely develop into SCC. Lichen planus is an uncommon condition diagnosed in between 2 in 1000 to 1 in 100 of the population. 4 in 10 people at a treatment centre for people with lichen planus had oesophageal lichen planus diagnosed by taking a biopsy. 6 in 100 of those diagnosed with oesophageal lichen planus went on to develop SCC. This is a rare cause of SCC in the UK.

Adenocarcinoma

- Tobacco use increases the risk of adenocarcinoma.

- People with certain conditions are slightly more likely to develop adenocarcinoma. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is one such condition. GORD develops in up to a third of people who have a weak lower oesophageal sphincter (valve). This weakness lets acidic stomach contents splash back up into the oesophagus. It causes heartburn and reflux. The risk of cancer increases slightly if GORD is severe and long-term. Most people with GORD will not have cancer.

- Barrett’s oesophagus is another condition that might increase the risk of cancer. It is when some of the cells in the oesophagus grow abnormally. Most people with Barrett’s oesophagus will not have cancer. The amount of acid reflux and the duration of acid exposure are key risk factors. 1 in 10 people with reflux (GORD) will develop Barrett’s Oesophagus. Of those with Barrett’s Oesophagus, between 3 in 1,000 and 6 in 1,000 people may develop oesophageal cancer, per year. Over a person’s lifetime, the risk of developing oesophageal cancer is 7.5% to 12.5%. The risk depends on several factors, including how long Barrett’s has been present and whether there are changes to the cells (dysplasia).

- A family history of oesophageal cancer can increase the risk to a small extent.

- Having a higher than healthy body weight is a risk factor in 1 in 4 oesophageal cancers.These figures are relating to a body mass index (BMI) of 30Kg/m2 or more. The higher the BMI, the greater the risk. A higher BMI increases reflux and Barrett’s oesophagus. This increases the risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. You can check your BMI using the online tool found on the NHS website.

- Achalasia can also increase the risk of developing adenocarcinoma.

Symptoms

What are the symptoms?

Oesophageal cancer may cause no symptoms until it blocks food and fluids from passing to the stomach. Some people report long-lasting heartburn and indigestion before other symptoms.

Symptoms include the following:

- Difficulty in swallowing (also known as dysphagia). This symptom starts with solid foods and progresses to liquids as the cancer worsens.

- Pain when swallowing, pain behind the breastbone, or upper belly pain.

- Weight loss without trying.

- Regurgitation of food or being sick (vomiting) after eating or drinking.

- Regurgitated food containing blood.

- Vomiting blood.

- Choking, unexplained dry persistent coughing or unexplained chest infections.

- Feeling tired, which can be related to anaemia. Anaemia is when you have low levels of healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen throughout your body.

- A blood test may show a high platelet count (reactive thrombocytosis) that might be associated with cancer.

Diagnosis

How is the diagnosis made?

Most people seek medical help due to swallowing problems. It’s important to see the doctor early when symptoms start. This increases the chances of a quick diagnosis and effective treatment. We encourage everyone to seek help, as treatments can help reduce symptoms, even if they can’t cure the cancer. Your GP is likely to make a referral to a specialist for investigations. The test used to diagnose oesophageal cancer is likely to be an endoscopy. A narrow, flexible pipe is passed gently into the oesophagus through the nose or mouth. This uses a local anaesthetic throat spray or sedation. The doctor can see changes in the oesophagus lining and take tissue samples (biopsy) for lab tests. The tests can help decide whether it is cancer and what type of cancer it is.

If cancer is diagnosed, other tests may be needed to see if it has spread. These include chest X-ray and an ultrasound chest examination. Doctors may also use other tests, such as a CT or MRI scan, to find out where the cancer is and if it has spread. These types of scans detect changes to body and organ structures.

A CT scan is sometimes combined with a PET scan. PET stands for positron emission tomography. It detects tiny changes in body cells using a radioactive drug. This drug shows where the cancer is more active in the body. Sometimes, doctors use an endoscope with an ultrasound device at its tip. This is called an endoscopic ultrasound. It checks areas inside the body from the oesophagus.

Occasionally, a surgeon must look inside the belly (abdomen). Surgeons call this surgery a laparoscopy. They use a special illuminated tube to check for cancer spread.

Treatment

The treatment pathway will be decided by a multi-disciplinary team (MDT). The team consists of several practitioners including a consultant oncologist, clinical nurse specialist, dietitian, physiotherapist and others when needed.

Endoscopic mucosal resection: This treatment is like having an endoscopy. Doctors use this treatment to remove abnormal cells lining the oesophagus. It is used for very small cancers, found only on the surface of the oesophagus.

Surgery: An oesophagectomy is the most common treatment in the UK. This is true if the cancer has not spread beyond the oesophagus. The type and position of the tumour, and the person’s health, may affect the decision to operate. Only 3 in 10 people with oesophageal cancer are fit enough to undergo an oesophagectomy. Others may have advanced cancer diagnosed and the available treatments are found on page 7.

Preparing for surgery (prehabilitation): An oesophagectomy is major surgery and it won’t suit everyone. It is important to be fit for the surgery. So, prehabilitation (or prehab) may be offered to prepare for it. This may involve therapists, such as dietitians and physiotherapists, to give advice and support. Prehab lets people having surgery improve their nutrition and fitness before their operation. Research has shown that prehab improves body strength and helps people cope better with surgery. Ask your doctor if this is available.

During surgery: An oesophagectomy is the removal of the cancerous part of the oesophagus. The surgeon may need to enter the chest cavity, abdomen, or neck. The approach can vary from keyhole surgery, including robotic assisted surgery, to larger open surgery. It depends on the cancer’s location and spread to nearby lymph nodes. The surgery aims to remove the cancer. It also removes nearby lymph nodes and tissues that the cancer may have spread to. This gives the person the best chance of survival. A tube is then made from the stomach. The stomach is then drawn up into the chest or neck. There, the surgeon joins the stomach to what remains of the oesophagus.

After surgery: After oesophagectomy, people are usually cared for in an intensive care ward. The person’s diet and the texture of the food they eat may change at first while the surgical joins (anastomosis) heal. Some people may need a short-term feeding tube placed through the skin into in their small bowel. It can help them keep their weight up as they recover from the surgery and start to eat again. Surgeons call this tube a jejunostomy. A dietitian will provide help and support if this is the case.

After recovery, most people can eat again. A person may eat less due to feeling full because their digestive tract doesn’t hold the same capacity for large meals. So, they often need to eat smaller meals more often. The person may need snacks between meals. A dietitian can help the person maintain their weight. Dietitians are an important part of the team, so ask your doctor for a referral.

Sometimes, swallowing problems can return weeks or months after the operation. Often, this is due to scarring (known as a ‘stricture’) where the surgeon has made the join (anastomosis). These strictures can be stretched using an endoscope. Sometimes a doctor might recommend more than one endoscopy procedure to resolve the stricture. These symptoms may also be because the cancer has returned. If you are having swallowing problems, contact your doctor.

Some people may experience dumping syndrome after surgery. Your dietitian can advise you about your diet in relation to this condition.

Radiotherapy: If surgery can’t safely remove the tumour, the doctor may use radiotherapy. Radiotherapy uses high-energy waves like X-rays to destroy cancer cells. Radiotherapy can cure early tumours, especially squamous cell cancer. Radiotherapy can also be used with chemotherapy and before surgery to shrink the tumour. It is also sometimes an alternative to surgery. When radiotherapy is given to try and cure the cancer, it is known as radical radiotherapy.

Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy uses drugs that work inside the body to destroy cancer cells (cytotoxic). Chemotherapy can be used alone or with radiotherapy (chemoradiotherapy). Either approach can shrink the cancer. Chemotherapy can be used before or after surgery. If used before surgery, it makes surgery easier and boosts survival rates. This is called neoadjuvant therapy. Chemotherapy can also be used alone if the cancer is small. This could cure it, but you will be monitored closely after treatment.

How is advanced oesophageal cancer treated?

As the tumour advances, it grows through the oesophagus. It can invade nearby tissues. It can spread to other areas of the body via the blood and lymphatic systems. This may have already happened when the cancer is first diagnosed or may happen later. Doctors call the areas where the cancer might have spread ‘secondaries’ or ‘metastases’. This is then called advanced, secondary or metastatic cancer.

The most common sites for advanced oesophageal cancer to spread to are:

- Liver

- Lungs

- Lymph nodes

- Bones

Recently, there have been many advances in treating advanced oesophageal cancer. Your clinical team will share more on the benefits and side effects of these treatments.

Endoscopic stent placement: A stent is used as treatment as part of palliative care. It doesn’t treat the tumour but does help to reduce symptoms. This treatment is to help people to eat and drink when they have advanced cancer. A stent is a tube. It is inserted into the oesophagus using an endoscope to keep the oesophagus open. This allows food and fluid to be swallowed easily. Manufacturers make these tubes from either plastic or springy metal coils. A stent is usually placed under sedation or anaesthetic in the endoscopy department. Large food particles and tougher foods, such as pieces of meat, can block them. So, the team always provide specific diet advice. Sometimes, these tubes cause troublesome heartburn and regurgitation. Acid-suppressing medicines can help reduce symptoms. If you still struggle with weight loss or eating, ask your consultant or GP for a dietitian referral.

Endoscopic laser treatment: A possible form of treatment, a specialist endoscopist will use a laser to destroy any tumour growing into the gullet. Some people must have combined laser treatment and intubation. This means a tube is placed in the gullet during treatment. It stops fluid from going into the lungs and causing an infection. This will need the person to have a general anaesthetic for the endoscopy.

Palliative radiotherapy: Radiotherapy in advanced cancer does not cure it, but it can control symptoms and prolong life. It aims to balance the side effects and the treatment’s benefits. It’s meant to treat the cancer’s symptoms. Its ability to shrink the size of the secondary cancer deposits seen on the scans allows for the measurement of its effects. In smaller doses, it’s called palliative radiotherapy. Palliative radiotherapy is sometimes used with chemotherapy to ease symptoms (chemoradiotherapy). Doctors can give radiotherapy as an external beam or inside the gullet using an endoscope. Doctors call this endoscopy treatment method brachytherapy.

Targeted therapies: Targeted therapies are a new type of treatment. One example is monoclonal antibodies that can target the cancer cells specifically. Other targeted therapies can stop the tumour from growing a new blood supply. These therapies are called angiogenic drugs. You will have tests to find out which of these treatments may work for you.

Immunotherapy: Immunotherapy treatment targets the immune system. It helps it to recognise and destroy cancer cells. This treatment is considered in specific cases where research shows a benefit. Ask your cancer doctor if you would benefit from this treatment.

Support

Specialist nurses, known as clinical nurse specialists (CNS), can be contacted for support before, during and after treatment. Your CNS will be able to give you information on what matters most to you.

Palliative care teams may help people with advanced oesophageal cancer who need palliative care for cancer-related symptoms. The goal of palliative care is to help those with serious illnesses live well. The team uses a whole-person approach. They help with:

- Decision-making

- Management of symptoms, for example, swallowing problems, vomiting and pain

- Spiritual and emotional support

They also provide advanced care planning. This helps the person consider and decide how to handle future health issues. This lets people be proactive about their future wishes.

The charity Macmillan offers information and support on all aspects of cancer. They have a helpline and written materials for those who have been diagnosed and their families. The Helpline telephone number is 0808 808 00 00 (open seven days a week, 8am to 8pm.) They also have information on advanced cancer on their website.

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provides guidelines for diagnosing and treating oesophageal cancer. You can read their recommendations online.

There is an ongoing audit for people with oesophageal, gastric, or oesophagogastric cancer. You can read more about it online.

You can find more information about oesophageal cancer from Cancer Research UK online.

Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) funded and created nutrition videos for people with oesophageal cancer. They worked with healthcare professionals, Guts UK, and other charities to make this happen.

The charity, the Oesophageal Patients Association, provides support for people diagnosed with oesophageal cancer.

What to ask my doctor?

- What treatment is best for me?

- Are there any specialist nurses who can help guide me through the diagnosis and treatment?

- Would I be able to be referred to a palliative care team if my cancer cannot be cured?

- Can I be referred to a dietitian for advice?

- Does the hospital have a prehabilitation scheme?

- Are there any research trials that I could take part in?

Watch our Barrett’s oesophagus webinar on demand

Discover more about Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal cancer and hear from healthcare professionals and people with lived experience of the conditions:

Research

Early diagnosis of oesophageal cancer

Guts UK is proud to fund oesophageal cancer research that will explore the use of breath-testing for pre-cancerous cell changes in people with Barrett’s oesophagus. If successful, this research could diagnose people with oesophageal cancer earlier.

Discover more:

Copyright © 2026 Guts UK. This leaflet was published by Guts UK in January 2026 and will be reviewed in January 2029. The leaflet was written by Guts UK and reviewed by experts in oesophageal cancer and has been subject to both lay and professional review. All content in this leaflet is for information only. The information in this leaflet is not a substitute for professional medical care by a qualified doctor or other healthcare professional. We currently use AI translation tools on our website, which may not always provide perfect translations. Please check for further explanation with your doctor if the information is unclear. ALWAYS check with your doctor if you have any concerns about your health, medical condition or treatment. The publishers are not responsible or liable, directly or indirectly, for any form of damages whatsoever resulting from the use (or misuse) of information contained or implied in this leaflet. Please contact Guts UK if you believe any information in this leaflet is in error.