Barrett’s Oesophagus

Download printable versionOverview

The oesophagus is also known as the gullet. In Barrett’s oesophagus, normal cells of the gullet change. They become cells that do not look normal. The abnormal cells replace the normal cells lining the oesophagus. Abnormal cells start where the oesophagus and stomach meet. They spread upwards from there. It’s possible for Barrett’s oesophagus to lead to cancer. This happens in a few people with this condition, but most people will not develop cancer.

Causes

Causes of Barrett’s Oesophagus

The exact cause is unknown, but it is strongly linked to long-term gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). GORD can cause the symptoms of heartburn and reflux. About 11 in 100 people with GORD will get Barrett’s oesophagus. That risk increases with the length of time people have symptoms. This risk also rises when symptoms happen more often. With GORD, acid and non-acid stomach juices leak or reflux into the oesophagus. The stomach contents inflame and injure the oesophageal lining. This is called oesophagitis.

Find out more about heartburn and reflux by visiting our online information. If you would like a copy, please email us at info@gutscharity.org.uk or call 020 7486 0341.

Over time, in some people with GORD, the lining of the oesophagus changes. The oesophagus lining can transform to resemble the bowel’s lining. This change is called intestinal metaplasia.

Other risk factors for Barrett’s oesophagus include:

- Older age.

- Being male. Barrett’s oesophagus is more common in white men.

- Family history of Barrett’s oesophagus.

- Having a higher than healthy body weight.

- Smoking.

- Being diagnosed with a hiatus hernia. A hiatus hernia is where the stomach abnormally extends from the abdomen into the chest.

Symptoms

What are the usual symptoms?

The main symptom associated with Barrett’s oesophagus is reflux. Reflux symptoms are:

- Heartburn (burning feeling behind the breastbone).

- Bringing food back up (regurgitation).

You may also have a metallic taste in your mouth or have a sore throat. This is worse after lying down because reflux is worse when lying down. Waking from reflux symptoms at night is a strong risk factor. Sometimes people with Barrett’s oesophagus do not report symptoms as their oesophagus is less sensitive to reflux. Ignoring symptoms or reflux or self-medicating with antacids can lead to delayed diagnosis.

Diagnosis

How is Barrett’s oesophagus diagnosed?

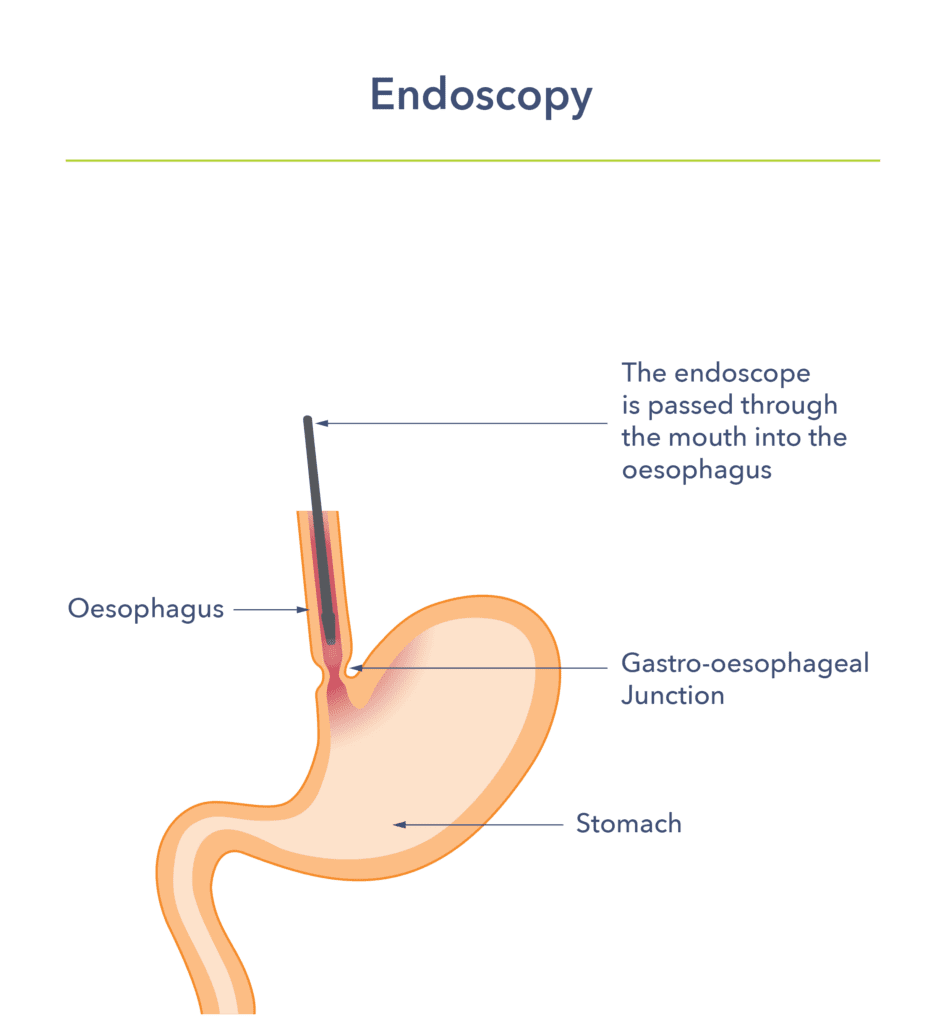

Endoscopy

Doctors diagnose Barrett’s oesophagus by looking at the oesophageal lining. They use a procedure called endoscopy. This is a test done by a doctor or clinical endoscopist (usually a specialist nurse). They use a small tube (the width of a small finger) with a camera on the end. They insert it into the oesophagus and stomach via the mouth. Local anaesthetic spray and sedation can be used to make the procedure more comfortable.

The area of interest is where the oesophagus meets the stomach, and it is called the gastro-oesophageal junction. Doctors identify Barrett’s oesophagus by its red coloured lining. It replaces the normal pink lining of the oesophagus. It goes from the junction up the oesophagus. Biopsies are then taken to confirm the diagnosis. A pathologist will identify the cells of Barrett’s oesophagus under the microscope. They also look for abnormal cells (dysplasia), which can be graded into low-grade or high-grade dysplasia.

Dysplasia increases the risk of cancer in Barrett’s oesophagus. If low-grade dysplasia is found, a repeat endoscopy in 6 months is ordered. This is to reassess and see if referral to a specialist centre for treatment is needed. Doctors quickly refer people with high-grade dysplasia to a specialist centre. This is because the risk of progression to cancer is higher.

A newer endoscopy method is called trans nasal endoscopy. The instrument is thinner and inserted through the nose rather than the mouth. This might be a more comfortable procedure. It is currently available in some centres but not all of them.

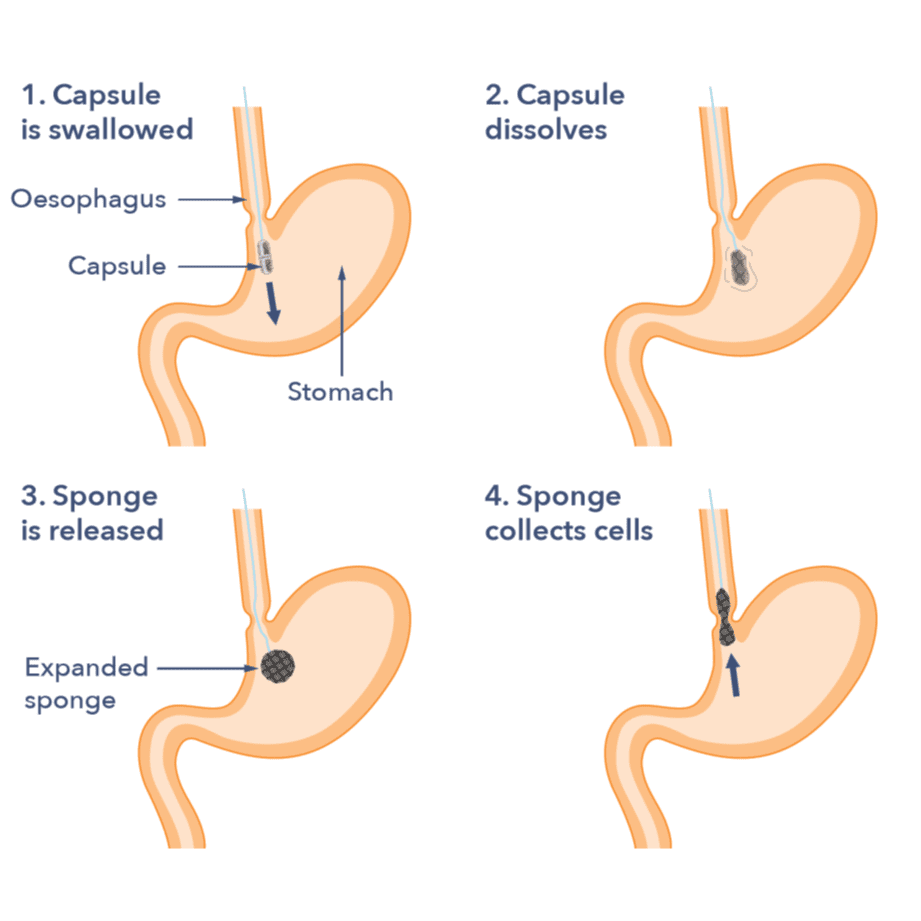

Capsule Sponge

The capsule sponge test is a new test that is available in some areas of the UK. It is used to find Barrett’s oesophagus in people who have persistent heartburn and reflux symptoms. When you have this test, you are asked to swallow a small capsule with a sponge inside. The sponge is attached to a piece of thread. The capsule dissolves in the stomach about seven minutes after you swallow it. Then, it releases the sponge inside. A nurse will then gently pull the thread to remove the sponge.

On the way out, the sponge collects cells from the lining. The cells are then checked in the lab. The goal is to see if there are any changes in the cells using a special stain called TFF3. If this does show cell changes, you will then be asked to attend for an endoscopy to confirm if there is Barrett’s present.

Understanding your endoscopy report

Your endoscopist will measure the Barrett’s oesophagus with a system called the Prague classification. The M shows the length of the Barrett’s segment, including any peaks, known as tongues. C refers to the length of the Barrett’s segment fully around the gullet. M5C4 means the Barrett’s is 5cm long at its longest point and is fully around the gullet for a depth of 4cm.

How does Barrett’s oesophagus affect you over time?

Most people with Barrett’s oesophagus have GORD symptoms, and usually they are controlled well with medications. Others may have symptoms despite medication and need surgery to prevent acid reflux or repair a hiatus hernia. In comparison to the general population, people with Barrett’s oesophagus are 30 times more likely to develop a type of oesophageal cancer called oesophageal adenocarcinoma. However, only 1 in every 300 patients with Barrett’s will develop this cancer each year. It is considered uncommon and a small risk.

What impact can Barrett’s oesophagus have on your life?

The diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus can affect a person in many ways. These include the impact on well-being due to the symptoms and fear of oesophageal cancer.

Watch out for these symptoms:

- Trouble swallowing.

- Frequent regurgitation of food or being sick (vomiting) after eating or drinking.

- Pain on swallowing.

- Weight loss.

- Anaemia (symptoms of feeling tired).

- Vomiting blood.

- Changes to your voice. This might involve having a hoarse voice.

If any of these are experienced, then a doctor should be consulted. Further tests may be done. If cancer is found, it may be treated endoscopically, with surgery, or with chemotherapy. Treatment depends on the stage of the cancer. The stage describes the tumour’s size and its spread outside the oesophagus.

Persistent reflux can sometimes cause an oesophageal stricture (narrowing of the gullet). This can make it hard to swallow. Endoscopy can treat strictures by stretching them.

There is also a fear of developing cancer. All these factors can cause great upset and feelings of hopelessness. If you feel any of these, tell your doctor. They can then offer support. Many specialist centres run nurse-led support groups. A support group lets you share information, advice and support.

Treatment

What treatment is available for Barrett’s oesophagus?

Barrett’s oesophagus without dysplasia (abnormal cells)

A person without dysplasia would be at low risk of cancer. People without dysplasia may be treated with these options below. However, these treatments do not remove Barrett’s oesophagus so, they do not eliminate the small risk of oesophageal cancer.

Medicines

The most used medicines for Barrett’s oesophagus are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Omeprazole and lansoprazole belong to this group, but there are others. They reduce stomach acid production. This, in turn, reduces acid reflux into the oesophagus. Some people who are intolerant to PPIs are recommended to have different medications, such as famotidine. These are usually well tolerated but much less effective than PPIs, especially in the long term. Medical treatment will be prescribed by your doctor. You should continue to take medical treatment if you have been diagnosed with Barrett’s oesophagus. There is ongoing research on drugs to prevent cancer progression, like aspirin and PPIs.

Lifestyle changes

These are all aimed at reducing acid reflux. They include:

- Weight loss

- Drinking less alcohol.

- Stopping smoking.

- Smaller meal portions.

- Not eating within three hours of bedtime.

Find out more about heartburn and reflux by visiting our online information. If you would like a copy, please email us at: info@gutscharity.org.uk or call 020 7486 0341.

Surgical options

If medication and lifestyle changes do not help, surgeons may undertake a laparoscopic (keyhole surgery) Nissen fundoplication. This is where the upper stomach is wrapped and stapled around the lower oesophagus.

Endoscopic options

Some younger people with very long segments of Barrett’s and a strong family history of cancer might be recommended to have endoscopic ablation of Barrett’s oesophagus (see below). However, this needs to be discussed with a specialist.

Barrett’s oesophagus with dysplasia (abnormal cells)

The treatment for Barrett’s oesophagus has changed a lot in recent years. Previously, people with high-grade dysplasia were either:

- Monitored closely until cancer was found, or

- Referred for surgery to remove the oesophagus.

Oesophagectomy is a major operation to remove the oesophagus. It is now mostly used for people with oesophageal cancer. Minimally invasive endoscopic therapy for Barrett’s has changed the management of early-cancer or high-grade dysplasia. It removes or treats the affected part of the oesophageal lining. Treatment is usually done at specialist centres with an endoscopic camera. The choice of procedure depends on various factors.

Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR)

This is a technique for removing small areas of abnormality from the lining of the gullet, stomach or duodenum.

EMR can assess the abnormal Barrett’s tissue better than a biopsy. So, it gives more information about the best treatment for you. At the same time, the EMR also treats the abnormal area. EMR removes pre-cancerous cells or small cancers. It does this without major surgery. It is usually done under sedation. When EMR is performed, there is a risk (approximately 1 in 50) of bleeding. If bleeding occurs, it will usually stop by itself, but a hospital stay may be needed to observe and treat it.

Rarely, a small hole can develop in the lining of the area removed (perforation). This happens in about 1 in 200 procedures. If this happens, it will mean a hospital stay for antibiotics and feeding, and maybe an operation to repair any damage. After the procedure, the scar will heal. It’s common to have some chest discomfort and pain when swallowing for the first 2 to 3 days. If this continues, or you have trouble swallowing, the scar may have narrowed the oesophagus. This occurs in about 1 in 20 people. An endoscopy can treat it by stretching the scar.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)

This removes early-stage cancer in the lining of the oesophagus. The treatment is like EMR but takes a longer time and carries a higher risk of perforation (1 in 50). It is done under a general anaesthetic. The doctor might recommend a short hospital stay after the ESD. This procedure is becoming more common, particularly for larger areas of abnormality.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA)

This is a technique that lets the endoscopist burn away the abnormal cells in the oesophageal lining. It is done under sedation. It is very safe and effective at removing abnormal cells, but it can only be used on flat areas. So, it is often used after EMR has removed any raised areas. The technique is often called HALO® RFA or Barrx®. There are different types of devices. The doctor will decide the best device for your type of Barrett’s. The choice depends on the size of the affected area. People often need several treatments to entirely remove the Barrett’s.

Radiofrequency ablation has been used for years in the UK, the USA and Europe for treatment. It is now the preferred first-line technique in the UK for high-grade dysplasia. NICE has also approved it for some patients with low-grade dysplasia.

Cryotherapy

This is a technique that lets the endoscopist freeze the abnormal cells. It is done under sedation. Like the RFA, it can only be used on flat areas. It has been used in the USA, the UK and Europe as part of research studies with good results. It is currently used in the UK as part of research studies, and your doctor might discuss participation in these studies if you are eligible.

Does Barrett’s oesophagus need to be monitored, and if so, how?

People are usually entered into a surveillance programme. It ensures regular monitoring, usually by endoscopy. Capsule sponge may also be offered instead of endoscopy for surveillance in some hospitals. During endoscopy, biopsies are taken to check the cells. Monitoring Barrett’s oesophagus is vital and must be as long as this is of potential benefit to the patient. A biopsy may find no dysplasia during one endoscopy, but this does not mean the person will never get dysplasia or cancer in the future.

However, this depends on fitness and other medical risks. Surveillance endoscopy frequency varies by person. It depends on the type and length of the abnormal lining seen. Guidelines suggest endoscopic surveillance plus biopsies should be done:

- Every 2 to 3 years in people with long-segment Barrett’s oesophagus. Long segment means a length of 3cm or more.

- Every 3 to 5 years for people with short-segment Barrett’s oesophagus with intestinal metaplasia. Short segment means a length of less than 3cm. Intestinal metaplasia means oesophageal cells that have changed to pre-cancerous cells.

An individual’s risk should factor in their age, sex and family history of oesophageal cancer. It should also consider their smoking history. So, the screening frequency could be adjusted.

People with short-segment Barrett’s oesophagus without intestinal metaplasia would not usually be offered endoscopic surveillance. This is because these people are not at increased risk of cancer. This diagnosis should, however, be confirmed with 2 endoscopies.

Support

What to ask your doctor?

- Are there any other medications I can try? If not, am I suitable for surgery?

- How often do I need an endoscopy?

- Is my ongoing surveillance appropriate?

- Is there a Barrett’s oesophagus patient support group or specialist nurse in my area?

Where can I get more information?

Guts UK Charity is a member of an organisation called Action Against Heartburn. The organisation provides links to other charities that can provide help and support.

Watch our Barrett’s oesophagus webinar on demand

Discover more about Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal cancer and hear from healthcare professionals and people with lived experience of the conditions:

Research

What further research needs to be done on Barrett’s oesophagus?

Several research areas are needed to improve the treatment of Barrett’s oesophagus. Early diagnosis is a key strategy in cancer research, and work using non-endoscopic methods to find Barrett’s includes saliva biomarkers and breath testing, as well as the newly introduced capsule sponge. Blood markers for the identification of Barrett’s oesophagus are also being considered, but much more research and trials are needed before these can be used.

There is also work needed to assess more accurately which patients are likely to progress to cancer, improving the quality of surveillance endoscopy and improving access to specialist centres for treatment.

Learn more:

Copyright © 2026 Guts UK. This leaflet was published by Guts UK charity in January 2026 and will be reviewed in January 2028. The leaflet was written by Guts UK and reviewed by experts in Barretts oesophagus and has been subject to both lay and professional review. All content in this leaflet is for information only. The information in this leaflet is not a substitute for professional medical care by a qualified doctor or other healthcare professional. We currently use AI translation tools on our website, which may not always provide perfect translations. Please check for further explanation with your doctor if the information is unclear. ALWAYS check with your doctor if you have any concerns about your health, medical condition or treatment. The publishers are not responsible or liable, directly or indirectly, for any form of damages whatsoever resulting from the use (or misuse) of information contained or implied in this leaflet. Please contact Guts UK if you believe any information in this leaflet is in error.